- Taylor Swift – Style – Qwanny’s Version | Q3 Media Super Bowl Ad

- 10 Greatest Wide Receivers that NEVER Won a Super Bowl

- 10 Best Christmas Day Performances in NBA History

- The Beast: The Final Fight | Documentary | A Qwality Film

- The Beast: The Final Fight Trailer

- The Crush Podcast: Broncos Lose Again, Kelce the Clout Chaser

- Qwality Sports: Ben Gordon Interview, Talks Time in NBA and His Workout Mindset

- AFC South Sports Betting Preview

- UFC London Aspinall vs Blaydes

- Take A Guess: The Sports Trivia Game Show Hosted by DeQwan Young | Episode 29

We.

- Updated: June 9, 2016

Sports are a magical thing. They mean so many things to so many people. For some, they are a way to advance one’s station in life. For others, they are a way to send a message and change the world. For some, they are simply entertainment. Sports give us so much; the highest of highs, the lowest of lows, and everything in between. They take otherwise ordinary people to heights unreachable and unimaginable and turn them into legendary figures, made immortal as the tales of their greatness get passed from generation to generation. They bridge those generations. They bring people together. Sports are what we love, what we watch, what we do, and what we are. They are a microcosm of society.

Many of us watch to be entertained. We leave the real world for a short spell and lose ourselves in a magic act. In those magic moments, we look for the trials and tribulations of the often-times crazy, frustrating world in which we spend most of our time to melt away. After all, the scoreboard is going to read 0:00 and the magic act ends and we go back to the crazy, frustrating real world with all its crazy, frustrating, unfortunately very much real problems. Part of the magic, though, is its ability to occasionally leave its magical realm and affect the crazy, frustrating, unfortunately very much real problems of the crazy, frustrating real world. Such was the case with a man from Louisville, Kentucky, named Cassius Clay, who changed his name to Muhammad Ali and changed the world into something a little less crazy and frustrating. And did it through sport.

The journey of the man who would become arguably the greatest boxer the world had ever seen started with a bicycle. At age 12, a young Ali, then known as Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., after his father Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., who was named after the abolitionist of the same name, had his bicycle stolen and told a responding police officer that he was going to “whup” the guilty party. That police officer, Joe Martin, was a boxing coach, who formally introduced Clay to the sport. Clay took to the ring like a fish to water, winning championships at all levels en route to qualifying for the 1960 Rome Olympics. In Rome, Clay won the gold in the light heavyweight division. However, upon his return to the United States, he was refused service at a lunch counter because he was black and learned very quickly that, while he may have just represented his country brilliantly, he was still a second-class citizen in the eyes of many he had just represented.

In 1964, a 19-0 Clay received a shot at the heavyweight championship of the world against Sonny Liston. Clay was a massive underdog against the heavy puncher, but pulled the upset and told all his doubters at ringside to eat their words and that he was the greatest. The next day, Clay changed his name to Cassius X, affiliated himself with the Nation of Islam, and shortly after, was given the name Muhammad Ali by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad.

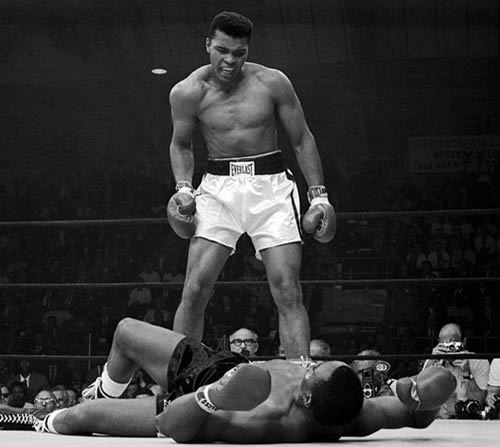

In a rematch with Liston in 1965, Ali won in two minutes after a short punch caught Liston and dropped him. There are differing opinions as to what happened, with some claiming that Liston took a dive. Others say Ali really caught him. As Nation of Islam minister Abdul Rahman put it “Ali hit him so fast, he didn’t really know he hit him.”

In February of 1966, Ali’s draft classification was changed from 1-Y, fit for service only in an emergency, where he was originally classified as the result of low IQ test scores, to 1-A, after the armed forces lowered their standards. Ali called himself a conscientious objector, citing his faith, and went on to say that he “ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” The WBA stripped him of their heavyweight championship. Ali attempted to set up a fight with new WBA champion Ernie Terrell, but due to Ali’s statements, multiple locations refused to hold the fight for one reason or another, including the fact that Ali technically wasn’t using his real name, the reason cited by the Illinois Athletic Commission. After a few fights abroad, Ali fought Terrell in Houston in February of 1967. Ali toyed with Terrell, making him pay for slights such as refusing to call him Ali, and regained the WBA championship. He would be stripped of the world championship again and would be denied a license to box in April 1967 after refusing to be inducted into the army. Ali was arrested for refusing induction and convicted in June of that year. Sentenced to five years in prison, Ali remained free after making bond and appealed his sentence. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, which ruled 8-0 for Ali in June of 1971 after it was decided that no reason was given for the denial of his request to be classified as a conscientious objector. His standing in the court of public opinion was still very mixed, however.

When Ali, then known as Clay, was fighting Sonny Liston, he was seen as the good guy. The “babyface,” to borrow a term from professional wrestling, which seems appropriate, since it was from professional wrestler Gorgeous George that Ali borrowed the braggadocio for which he would become famous. But look at how things change. It was all good against Liston, but when Ali took a stand for something he believed in, people turned on him. However, the arguments against Ali revealed far more about the character of the people making them than they did about Ali. People couldn’t handle Ali. They couldn’t handle the fact that this black Muslim refused to fall in line. They couldn’t handle that he was serious in his convictions, regardless of any conviction.

Ali returned to boxing in October of 1970 against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta. His case was still under appeal, though the public stance on the war had shifted considerably in the three-plus years since Ali refused to be inducted into the military. Ali’s first professional defeat came at the hands of Joe Frazier in March 1971. After an undefeated 1972, Ali lost to Ken Norton in 1973, then defeated him in a rematch, setting up a rematch with Frazier, with Ali won. After defeating Frazier, the next battle for Ali was against George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire in October of 1974. The Rumble in the Jungle. Ali wasn’t given much of a chance and, at first glance, it wasn’t hard to see why. Foreman was younger. Foreman was a heavy hitter. And that’s all well and good, and George Foreman’s one of the greatest to ever do it, but George Foreman wasn’t Muhammad Ali and if there’s one thing folks should have learned by then, it’s to never count Ali out.

Crowds flocked to Zaire, where Ali was a king. He was the people’s champion, met with adoring chants wherever he went.

“Ali, Bomaye.”

“Ali, Bomaye.”

In the ring, Ali let the power puncher throw, hoping that the stronger Foreman would tire himself out, a strategy people at the time thought to be crazy. It worked. Ali won.

After a few more wins, Ali fought a rubber match with Joe Frazier in October of 1975, the Thrilla in Manila. On a blistering day in the Philippines, both men gave their all. Ultimately, Ali won by TKO when Frazier’s trainers would not let him answer the bell for the 15th round with his eyes swollen shut. After a few more title retentions, a couple appearances in the world of pro wrestling; a skirmish with Gorilla Monsoon in the WWWF and an exhibition match with Antonio Inoki in Tokyo, and another win over Ken Norton, in 1976, Ali retired from boxing. The retirement didn’t last long, as Ali returned to the ring in May of 1977. In February of 1978, Ali defeated Leon Spinks to become the first man to win the heavyweight championship three times. He retired briefly again, only to come back to try to make it four against Larry Holmes in 1980. The fight was a train wreck. A shell of his former self, Ali lost by TKO when Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in round eleven. Following a loss to Trevor Berbick the following year, Ali retired for good.

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1984 and was an advocate for awareness throughout the rest of his life. Ali fought the disease as best he could, but in his later years, the toll it had taken on him was quite evident. A fighter to the end, he never gave up, but there’s one fight none of us are ever going to win, and on June 3, nature added another win to its unblemished record.

Asked by the crowd for a poem while speaking at a Harvard commencement ceremony in 1975, Ali delivered the shortest poem in human history, yet it was one that said quite a bit. “Me, We.” See, Muhammad Ali’s story is one that tells who we were and who we are. It tells how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go. As Americans and as people. It is a story of courage and conviction. Of strength and integrity. Of honor and pride. Of getting knocked down seven times and getting up eight. Of heroism. It is the story of a man who grew up a second-class citizen in his own hometown, represented his country brilliantly on one of the grandest stages known to man, then came home and found that country unwilling to have his back. The man born Cassius was a modern-day Caesar.

Today, we turn on the television or open up our web browsers and see any one of a number of talking heads debate a number of ridiculous topics like Cam Newton dancing or Richard Sherman talking or Marshawn Lynch not talking. One can only imagine what these same talking heads would have said about Ali. Ali certainly faced a ton of criticism in his day, and race relations have improved since then (not nearly enough, but any step forward is a welcome one), but journalistic standards have regressed massively, to the point where the people on TV often aren’t there because they provide an insightful point of view, or are great reporters, or ask tough questions, but rather do just the opposite in a shameful, yet unfortunately, all too successful, attempt to get people talking and drive up ratings. As it was, a handful of Chickenhawks criticized Ali after his death for being a “draft dodger,” which, of course, he was not. He could have easily stayed overseas or in Canada after one of his fights, and actually dodged the draft, but he did not. He stayed in his home country and accepted the incredibly steep consequences for taking a stand and doing what he thought was right. The reality of the matter is that few of us have even a fraction of the courage Ali did.

Through the magic of sports, Muhammad Ali made the world a better place. The legend of Ali will live on forever, the stories of his greatness passed down from generation to generation. He mesmerized a nation and inspired people too young to have ever seen him fight. (I had the above image framed on my wall in college.) He impacted so many lives in so many ways. In the ring, he was the bringer of violence, out of it, an advocate for peace. He was a global ambassador. He was the Black Superman. He was the greatest. Both inside the ring and out.

R.I.P. Muhammad Ali

1942-2016

Twitter: @KSchroeder_312

E-mail: schroeder.giig@gmail.com